-

Chapter 1: Introduction

-

Chapter 2: Background

-

Chapter 3: Administration and Scoring

-

Chapter 4: Interpretation

-

Chapter 5: Case Studies

-

Chapter 6: Development

-

Chapter 7: Standardization

-

Chapter 8: Reliability

-

Chapter 9: Validity

-

Chapter 10: Fairness

-

Chapter 11: CAARS 2–Short

-

Chapter 12: CAARS 2–ADHD Index

-

Chapter 13: Translations

-

Appendices

CAARS 2 ManualChapter 5: Case 1. “Matt” |

Case 1. “Matt” |

Matt is a divorced man in his early 30s with a history of variable academic performance and current underemployment. He was first evaluated in elementary school and received differentiated instruction through a combination of academic accommodations (504 plan) and enrichment through the district’s Academically and Intellectually Gifted program. Matt is seeking this evaluation to obtain documentation supporting his request for business school entrance exam (GMAT) accommodations.

This case study illustrates the following:

-

Example of condensing data from the computer-generated Overview section into a data table for a clinical

report

-

Integrating childhood history with adult presentation

-

Administering CAARS 2 prior to the diagnostic interview

-

Interpreting borderline DSM T-scores and Symptom Counts

- Using Response Style Analysis to consider possible threats to validity

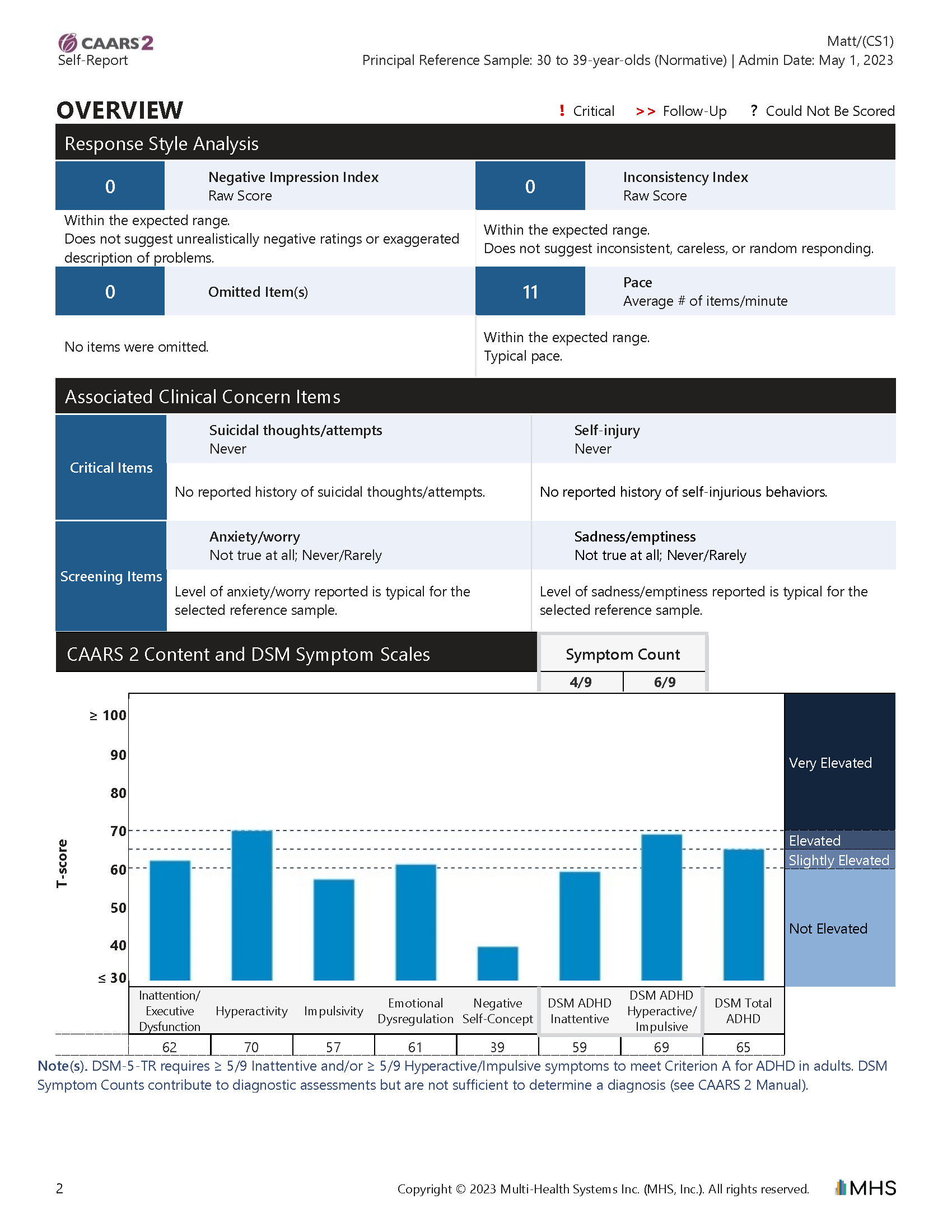

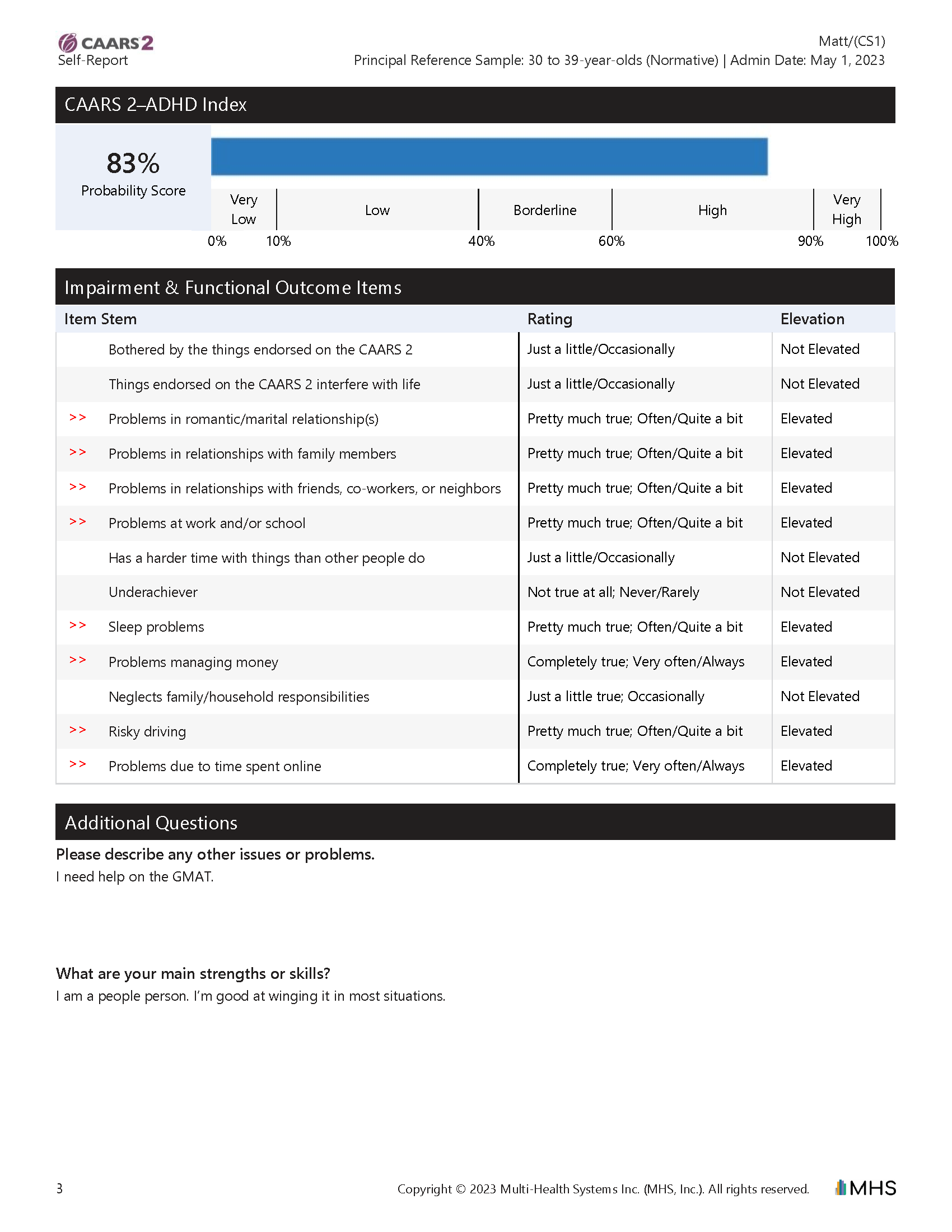

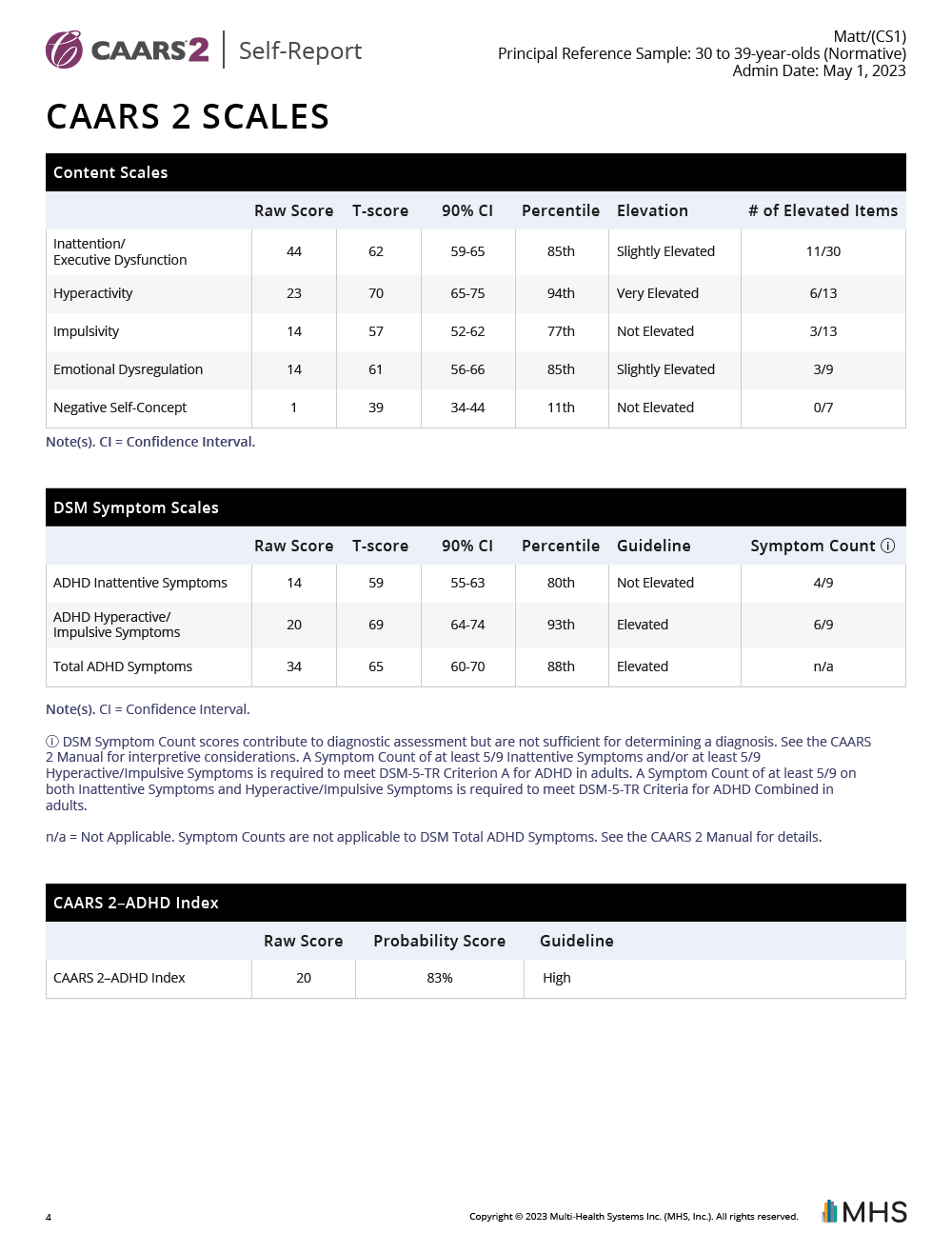

The clinician sent Matt a link to complete the CAARS 2 Self-Report in advance of the clinical interview, to help her identify which areas to target in their meeting. At Matt’s request, the clinician sent his girlfriend, Dyna, a link to complete the CAARS 2 Observer form (a signed release of information form was on file). Additional observer data were not available because Matt rarely saw his parents and he worried about negative repercussions if his manager found out he was getting an evaluation. The Overview and CAARS 2 Scales sections of Matt’s full-length CAARS 2 Self-Report is presented in Figure 5.1; the clinician-created data table excerpted from the report (showing self-report and observer data) is provided in Figure 5.2.

| Click to expand |

Figure 5.2. Sample Clinician-Generated CAARS 2 Data Table: Case Study #1–“Matt” (Normative Sample–Combined Gender)

|

Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales, 2nd Edition (CAARS 2) |

Self-Report | Observer | |

| Content Scales |

Inattention/Executive Dysfunction |

T = 62 | T = 74 |

| Hyperactivity | T = 70 | T = 77 | |

| Impulsivity | T = 57 | T = 65 | |

| Emotional Dysregulation | T = 61 | T = 71 | |

| Negative Self-Concept | T = 39 | T = 61 | |

| DSM Symptom Scales |

ADHD Inattentive Symptoms |

T = 59 Symptom Count = 4/9 |

T = 71 Symptom Count = 8/9 |

|

ADHD Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptoms |

T = 69 Symptom Count = 6/9 |

T = 77 Symptom Count = 8/9 |

|

| Total ADHD Symptoms | T = 65 | T = 75 | |

| CAARS 2–ADHD Index | ADHD Index |

Probability Score = 83% |

Probability Score = 98% |

The clinician followed the CAARS 2 Interpretation Guidelines (see chapter 4, Interpretation, and appendix D) to better understand Matt’s self-report data in preparation for their upcoming interview. She selected the default Combined Gender Normative Sample (age group = 30–39 years).

-

Examine the Response Style Analysis. The Response Style Analysis does not raise concerns about how Matt

approached completing the CAARS 2. Both validity indices (Negative Impression Index and Inconsistency Index) are

within the expected range. There are no Omitted Items. Pace was typical.

-

Examine the Associated Clinical Concern Items. None of Matt’s responses to the Associated Clinical

Concern Items indicate the need for follow-up. He reported no history of suicidal ideation or attempts,

self-injurious behaviors, or of feeling anxious/worried or sad/empty more than rarely.

-

Interpret the CAARS 2 Scales. Overall, some of Matt’s self-reported Content Scales are higher than

expected relative to other 30- to 39-year-olds. Specifically, his scores are Very Elevated for Hyperactivity,

and Slightly Elevated for Inattention/Executive Dysfunction and Emotional Dysregulation. His Impulsivity and

Negative Self-Concept scores are Not Elevated. Matt’s overall report of symptoms associated with DSM ADHD

is

higher than typically reported by 30- to 39-year-olds. He reported higher levels of hyperactive/impulsive

symptoms than typically reported by similarly-aged individuals, but his report of inattentive symptoms is no

higher than typical. He responded “often” or “very often” to 4 of the 9 inattentive features, and 6 of the 9

hyperactive/impulsive features. Matt’s DSM Total ADHD Symptoms T-score is also elevated,

suggesting his level of

ADHD symptoms is higher than what is typically reported by 30- to 39-year-olds. Matt’s CAARS 2–ADHD Index

probability score was in the High range, indicating that his scores have similarity to individuals diagnosed

with ADHD and are dissimilar to scores from individuals in the General Population Sample.

Looking across the profile of Matt’s CAARS 2 Scales, his Content Scales and DSM Symptom Scales are pretty consistent. The Hyperactivity Content scale and DSM ADHD Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Symptoms scale are both elevated, although the Impulsivity Content scale is not elevated. The Inattention/Executive Dysfunction scale is Slightly Elevated compared with the DSM ADHD Inattention Symptoms scale, which is not elevated, but the difference of 62 versus 59 indicates it is not a meaningful difference. Within the DSM Symptom Scales, there is agreement between T-scores and Symptom Counts. His DSM Total ADHD Symptoms T-score is elevated like his DSM ADHD Hyperactive/Impulsive Symptoms T-score and ADHD Index, although his DSM ADHD Inattentive Symptoms T-score is not elevated.

-

Item-level responses. The clinician reviewed the Items by Scale tables for the Content and DSM

Symptom

Scales in the CAARS 2 Single-Rater Report. Matt endorsed moderate to high levels of many features of

inattention/executive dysfunction, with a number of 2s (“Pretty much true; Often/Quite a bit”) and 3s (“Completely true;

Very often/Always”), but he only met the DSM criterion of “often” on 4 of the 9 Inattentive symptoms. The

clinician then turned back to the Overview section to review individual Impairment & Functional Outcome

Items.

She noted that Matt had elevated ratings (i.e., item-level responses were higher than typical for 30- to

39-year-olds) for these items: sleep problems, problems due to time spent online, problems with money

management, and risky driving. She flagged this section to consider as possible evidence of impairment and

possible treatment targets. The clinician reviewed the Elevation information for these items and noted that

Matt’s level of endorsement for sleep problems was uncommon for 30- to 39-year-olds in the normative sample. She

made a note to administer the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance–Short Form 8a to gather additional information about

possible sleep disruption. She noted that Matt indicated that he “often” experiences general problems at

work/school and in relationships. Matt’s responses to the Additional Questions included other

issues/problems,

“I need help on the GMAT,” as well as strengths/skills, “I am a people person,” “good at winging it.”

- Integration of CAARS 2 data. In general, Matt’s elevations on the Content Scales corresponded with his DSM Symptom Scales T-scores, reflecting prominent features of hyperactivity, as well as features of inattention, executive dysfunction, and emotional dysregulation. The elevated ADHD Index indicated a high similarity to individuals who have ADHD (as compared with individuals in the General Population Sample). The clinician noted that Matt described many features of hyperactivity with fewer examples of impulsivity, adding that it would be helpful to corroborate his self-report with other sources of information, such as information from observers and/or clinical observations during the interview. The clinician decided to follow up on the sub-clinical DSM ADHD Inattentive Symptom Count and get more information regarding if these symptoms might be masked in Matt’s current setting and whether there was evidence of them in his history.

The clinician began reviewing Dyna’s Observer ratings and noted the need for follow-up of the flagged Negative Impression Index as it may reflect an attempt to present an unfavorable impression of Matt. She checked the Interpretation chapter in her CAARS 2 manual for guidance and read, “Although an elevated Negative Impression Index score does not immediately invalidate results from the CAARS 2, it should prompt a review of the constituent items … Proceed with interpretation, remembering that the scores may over-represent areas of concern.” The clinician deferred further interpretation of the Observer ratings until she reviewed additional sources of information to help guide her as to how best to proceed.

During the initial meeting, the clinician gathered information about Matt’s background while listening for examples of possible ADHD in his school, relationship, and work history and observing him carefully for potential features of ADHD. Matt had one prior evaluation in the 4th grade, which led to him being identified as Academically and Intellectually Gifted, due to his exceptionally high Full-Scale IQ score and academic achievement testing scores. Other results from that evaluation, including parent and teacher-completed Conners Rating Scales (Conners, 1997), led to a diagnosis of DSM-IV ADHD, Hyperactive/Impulsive type, and the creation of a Section 504 plan with accommodations including extended time, preferential seating, parent/teacher monitoring of homework, and a positive reinforcement behavior chart. During middle school, Matt began struggling with tracking different assignments and due dates from multiple teachers. Missing, late, and incomplete work contributed to his poor grades. Matt’s parents met with a psychiatrist to discuss a medication trial, but they decided to increase his academic support instead. They hired a private tutor to help him stay organized and increased structure and supervision for homework and test preparation. These external supports helped Matt succeed in middle school and high school. He earned mostly As and Bs on his final report cards each year, and his 504 plan was discontinued. As Matt entered college, he convinced his parents that he wanted to attend without any accommodations or supports. His college transcript reflected mostly Cs. In an interview, Matt explained that his week-to-week grades fluctuated because he would procrastinate and avoid schoolwork for weeks at a time, then spend a weekend immersed in a major project or paper to get a high A on that particular assignment and pull his course average up to a C. He often pulled all-nighters before exams, in an attempt to learn an entire semester’s worth of information in a single night. Matt changed his academic major several times, often after withdrawing from a required course that he was going to fail. He graduated from college after six years with a major in Communications.

Matt is recently divorced from his wife of seven years. He said, “I really don’t know what happened. We used to have a lot of fun, but then it was just nagging all the time, constant complaining about you said you’d do this, you’re always late, yada yada yada.” He said he was surprised when his ex-wife asked him to move out, but that “it was her loss.” He quickly returned to the dating world a few months ago and met Dyna, whom he describes as “fun and supportive, she’d do anything for me … but we’re not too serious.” Matt noted that he tends to stay up late gaming and chatting with his friends online, so it is hard to get up in the morning and sometimes he is late to work. He clarified that he has plenty of money, but he has to pay late fees from time to time. He said he has, “a couple of minor fender-benders each year, but nothing major.”

For the last two years, Matt has worked as a crew supervisor for a commercial moving company. He described that his manager “helps keep me on track” with a detailed punch list before each move and a walk-through after each move. The information gained from the interview and a review of past performance evaluations suggested that Matt was less successful in prior jobs with limited oversight, such as sales positions where his coworkers resented covering for him when he forgot appointments or neglected to submit necessary paperwork (although the clients loved his engaging personality). Matt has grown tired of the monotonous nature of his current job and is applying to business school so he can increase his salary and “do something that uses my brains.” He took the GMAT once but did not score as well as he had hoped. Matt’s mother suggested that he should request extended time, like he used to get in school. When Matt submitted his 4th-grade evaluation with his application for GMAT accommodations, they requested current documentation of ADHD and how it impacts his performance as an adult.

After reviewing GMAT accommodation guidelines, the clinician evaluated IQ, academic achievement, and attention, being intentional about including timed tests (such as academic fluency tests) that would allow her to comment on whether extended time was an appropriate accommodation. Matt’s results were generally consistent with his 4th-grade evaluation, indicating above-average intellectual abilities and academic achievement. He scored in the impaired range on tests of sustained attention. Matt also did poorly on tests of academic fluency (involving both speed and accuracy); although he seemed capable of completing items on the fluency tests, his score dropped due to “careless” errors and long completion times as he periodically drifted off task. Behavioral observations included that Matt seemed restless and impatient, often interrupting the evaluator’s instructions. Although he was an interesting conversationalist, he often strayed far from the subject and needed frequent reminders to continue working.

The clinician again reviewed the CAARS 2 Self-Report results and judged them to be consistent with interview data, testing scores, past report cards, job performance evaluations, and behavioral observations. The clinician summarized that Matt shows a lifelong, persistent pattern of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that adversely impact his functioning in home, school, and work settings. These symptoms interfere with and reduce the quality of his current occupational functioning, and adversely impacted his past academic functioning and relationships. His presentation is not better accounted for by another diagnosis or explanation, and no secondary diagnosis is necessary to account for his current symptoms. The clinician diagnosed Matt with DSM-5-TR ADHD, Combined presentation, relying on past report cards and performance reviews to provide evidence of impairment across settings. She noted that his current work environment with high levels of structure and supervision (and low levels of cognitive demand) mitigated the expression of his symptoms and contrasted that with his work experiences in less structured/supervised settings where features of inattention were more impairing. The clinician noted that ADHD Combined represents a shift from Matt’s childhood diagnosis of ADHD Hyperactivity/Impulsivity, perhaps reflecting that his features of inattention became more evident as cognitive expectations increased beyond his ability to compensate with high intellectual abilities.

The clinician returned to the interpretation of Observer data provided by Matt’s girlfriend, Dyna, which had been set aside given the elevated Negative Impression Index. Most of Dyna’s ratings were higher than Matt reported. The clinician asked Matt about this pattern when he returned for a feedback session. Matt explained, “Yeah, Dyna just really wants me to get help. She worries that I downplay everything.” A careful review of the items on the Negative Impression Index in the context of interview data, record review, and qualitative clinical impressions suggested that these ratings represented exaggerated descriptions of actual problems, perhaps driven by Dyna’s zeal to make sure Matt received the accommodations he needed to succeed. The clinician proceeded with reviewing other data from the Observer form, keeping in mind that some of the values could be exaggerated. She noted similarities between self-report and observer data, including elevations for Hyperactivity, Inattention/Executive Dysfunction, and Emotional Dysregulation. She compared the two sets of scores to identify where they were statistically different from each other and found Dyna had much higher elevations than Matt for most of the scores. Dyna’s description of impulsivity matched the clinician’s observations during the evaluation. The clinician wondered if Matt’s confident presentation might mask underlying features of negative self-concept as endorsed by Dyna. Given the many sources of data supporting a DSM diagnosis of ADHD Combined, the clinician felt comfortable proceeding despite the elevated Negative Impression Index from Dyna’s Observer report.

The clinician’s assessment report summarized the reasons she assigned a diagnosis of ADHD, Combined presentation, and provided a variety of recommendations. Instead of recommending the requested accommodation of extended time, she recommended additional stop-the-clock breaks to allow Matt to walk around or stretch as needed without being penalized for losing time. She also recommended testing in a private setting so Matt would not distract or be distracted by other test-takers. In addition to responding to Matt’s request for accommodations on the GMAT, the clinician talked with him about supports that could be helpful at work and school. She referred him to a local psychiatrist with experience helping adults with ADHD to discuss medication options. She recommended that he work with a GMAT tutor to practice pacing himself and being strategic. She suggested that after the GMAT, he might want to meet with a therapist to consider ways he might extend his good “first impression” skills into long-term relationships. The clinician anticipated that business school could be challenging for Matt and outlined study strategies for him to try. She also summarized Matt’s pattern of strengths and challenges, so that he can be a strong self-advocate when he enters a more challenging work environment.

| < Back | Next > |